Blog

Ornamental Futures: Decentralization and Diversity

As we navigate the complexities of an era marked by societal transformation, architecture has the unique opportunity to embody a new vision for the future. This period of crisis—shaped by political, economic, social, and climate challenges—demands a departure from centralized power structures toward a decentralized approach where power, design, and agency are distributed across smaller, localized hubs. Architecture can act as a profound statement of resilience, diversity, and the human need for community, embracing principles that reconnect us to our environments and to one another.

Decentralization in architecture offers a break from the sterile uniformity that often defines centralized urban landscapes—rigid grids of towering glass skyscrapers focused on efficiency and productivity. Such homogenous environments can strip cities of their sense of place and individuality. In contrast, decentralized cities present dynamic, living systems that adapt organically to the diverse needs of their inhabitants. These urban spaces thrive as vibrant, localized hubs where each neighborhood cultivates its own architectural character, drawing from local culture, materials, and community involvement. This shift aligns with generational cycles of stability and conformity giving way to periods of individualism, fragmentation, and renewal in response to crises.

A key component of decentralized architecture is diversity—reflected not only in the physical appearance of buildings but in the cultural and social values they represent. Ornamentation plays a crucial role in this vision. Far from being mere decoration, it adds layers of complexity, depth, and history, anchoring architecture to the people and stories of the communities they serve. Through intricate facades, handcrafted details, or the use of locally sourced materials, ornamentation becomes a bold expression of autonomy, local pride, and diversity. In these decentralized spaces, every building tells its own story, celebrating the rich heritage and cultural distinctions of the people who live within and around them—a powerful counter-narrative to the uniformity of globalized aesthetics.

This emphasis on local identity and cultural diversity extends beyond aesthetics. It is central to fostering a true sense of place and belonging. Ornamentation in decentralized architecture can reflect sustainable practices, such as the use of traditional materials, passive solar design, or locally sourced building techniques. This approach not only contributes to resilience in the face of environmental and social challenges but also connects architecture to local ecosystems and histories. Each building becomes a symbol of sustainable, community-driven living, embodying harmony with nature, beauty, and the diverse cultures that shape these environments.

Diversity in decentralized architecture is also expressed through the variety of scales and forms that reflect the multifaceted nature of human life. Unlike the monumental, impersonal skyscrapers of centralized cities, decentralized spaces offer smaller, more intimate designs that prioritize human interaction and community connection. Homes, markets, public spaces, and workplaces are crafted to encourage collaboration, with ornamentation enhancing a sense of warmth and human presence. This rich tapestry of scales reflects a deeper philosophy about the future—one that values human connections, local craftsmanship, and sustainable living over corporate efficiency and uniformity.

The celebration of diversity in architecture also means acknowledging and incorporating the histories and voices of marginalized communities. Decentralized cities can serve as inclusive environments where diverse cultural identities, histories, and traditions are preserved and elevated. Architecture becomes a medium for social equity, providing platforms for underrepresented voices to shape the future of their communities. By engaging in participatory design and involving local residents in the architectural process, we can ensure that cities not only reflect a broader range of identities but also create spaces that are inclusive, accessible, and deeply connected to the people they serve.

As we move forward, embracing decentralization and diversity in architecture offers a path toward a more resilient and humane future. This vision rejects the impersonal, monolithic structures of centralized power in favor of human-scale, community-driven, and culturally rich design. In this decentralized future, architecture celebrates creativity, diversity, and autonomy—empowering communities to shape their own environments. By reflecting the unique stories, cultures, and aspirations of local populations, architecture has the potential to transform cities into living, breathing expressions of diversity and resilience, pointing toward a future where beauty, community, and belonging coexist in harmony.

This approach not only addresses the pressing challenges of today but also offers a hopeful, inclusive, and sustainable vision for tomorrow—one where diversity thrives in every corner of our built environment, and where architecture plays a central role in shaping a more equitable and connected world.

Gravity and Grace

There’s a natural force in reality that can push us beyond ourselves, opening up the chance for transformation and joy. Simone Weil called this “grace” — the opposite of gravity. Gravity is the force that represents the limits and necessities of the physical world. When we’re stuck in gravity, we feel incomplete, often leading to suffering, because we get caught up in the everyday grind and miss out on the bigger picture of love and connection.

But grace is different. It helps us break free from those limitations, offering us a way to see the world from a new perspective. While gravity keeps us focused on survival, grace lifts us, helping us move beyond ourselves and connect with something bigger.

When we give in to grace, the weight of gravity fades. We realize that transformation isn’t just possible — it’s part of life. This shift helps us connect with each other and experience joy in ways that are often overlooked. Architecture can do something similar. It can create spaces that pull us out of the mundane and remind us of the joy and connection that’s possible when we’re truly present.

In my work, I aim to design spaces that lift you break through the weight of daily life and invite transformation. Spaces that inspire joy, connection, and a sense of openness.

Democracy: A Common Good

Democracy is more than a political system—it is a moral and spiritual law that guides how we live together, balancing individual freedom with the pursuit of the common good. At its heart, democracy believes that when people are given the freedom to make choices, and they act with responsibility, the collective benefits. It’s about more than majority rule; it’s about shared responsibility and mutual respect for the well-being of all.

In this sense, democracy is not about chaos or unrestricted freedom, but about finding harmony between personal autonomy and the common interest. Just as in life, where we all agree to drive on the same side of the road for the sake of order and safety, democracy thrives on shared principles that allow individuals to pursue their goals without infringing on the rights of others. These shared agreements are not limitations but pathways to greater freedom, as they create the structure needed for everyone to thrive.

In architecture, this moral aspect of democracy is reflected in the spaces we design. Buildings and public spaces are not just for the individual—they serve the whole community. A structure designed with the collective in mind fosters connection, beauty, and functionality for all. Rules, like zoning laws or safety codes, ensure that these spaces function well, just as shared democratic principles ensure that society runs smoothly. Yet within those structures, there is room for creativity, expression, and innovation—just as democracy allows personal freedom within a framework that supports the common good.

True democracy, like well-designed architecture, brings order and harmony without stifling individual creativity. It encourages us to use our freedom not selfishly, but in a way that uplifts everyone. By respecting the needs of the whole, we build spaces—and societies—where both individual and collective aspirations are fulfilled.

Artificial Culture and Natural Intelligence

“Knowledge doesn't really care. Wisdom does.” ~ The Tao of Pooh, Benjamin Hoff

Artificial intelligence a complex adaptive system with trade-offs between efficiency and resiliency. What is especially unique with this technology is that for the first time in history, we have a technology that can transcend our existence and ask what makes us human?

In the past, technology has often been a driver of cultural change. For example, the invention of the printing press led to the spread of literacy and the rise of the Renaissance. The invention of the telephone and the internet have revolutionized the way we communicate and interact with each other.

Architecture is a form of cultural production that is often down stream of technology. Culture is a form of collective intelligence resulting from the distributed cognition of members of a society. Although maybe intelligent, culture is not always wise. With the rise and threat of artificial intelligence, it’s important to ask what makes us human? Are we able to coexist and harmonize with an intelligence greater than ours? How can we use this technology for our existential benefit? Typically, the same technology that have made us productive in the past had harmful and deceptive effects on humans. Design is not always benevolent; it can be used to control or empower us. We are not simply biological creatures. We are also designed creatures. Our bodies, our minds, and our culture are all shaped by design.

Since we are participating in this process of unfolding, we cannot turn towards history (or religion) for the existential question of our nature because for the first time this technology knows more about us then we know about ourselves. Imagine a god-like power of remembering all things and having infinite access to information? It still feels highly likely that today’s artificial intelligence is still ultimately finite. These systems have been trained on human data that is similar to our traditional generation to generation inheritance of knowledge, but at cyberspeed. These forms of intelligence will eventually begin to evolve on their own and, like human, begin to dream and be creative.

How can we grow an intelligence that aspires wisdom and cares. Will artificial intelligence become a tool for us to transcend in so far as they are aiming for self-transcendence themselves? For the architect Louis Sullivan, “nothing is really inorganic to the creative will.” What makes us human is our ability to act, the free will of choice, and the impulse to create. We have seen other species dance and sing, but not until artificial intelligence have we seen another form of intelligence write complex poetry. What used to distinguish humans was our ability to act using reason. Now artificial intelligence has shown the ability to use reason, but it remains to be seen if it can be wise.

Strong Towns in the Age of Resilience

Growth is an old paradigm. In most cases today, we need stability. Stability is an inherent feature of complex adaptive systems. The trend of reducing risk and maximizing efficiency has resulted to the fragility of our current systems, and now our struggle is to make better use of what we have already developed, making them capable of responding to difficulty by adapting to local conditions in order to harmonize the whole.

In complex systems, whether buildings, cities, or other environments, perfection is not possible with so many competing objectives. Instead, what we can strive for is a degree of stability and wholeness through an incremental process of adaptation that responds from the bottom up.

“…innovation that happens from the bottom up tends to be chaotic and smart. Innovation that happens from the top down tends to be orderly but dumb.” ~ Strong Towns: A Bottom Up Revolution to Build American Prosperity by Charles Marohn

One way we can strengthen the ability to bounce back from shocks of volatility is through developing more distributed renewable energy networks or microgrids. These systems can help us reduce reliance on centralized power grids that are vulnerable to disruptions. This decentralized approach adapts our communities in a way that minimizes dependencies on external systems. New forms of network connectivity can further help us communicate and cooperate more effectively during moments of disaster. By incorporating these ideas into our planning and development, we can create more resilient communities that are better able to withstand shocks and stresses.

The future will always remain unpredictable. By maintaining our existing infrastructure, our buildings and network systems can learn to adapt by making small incremental changes over time instead of attempting to complete our structures and systems to a complete state that attempts to resolve all future issues.

Bullshit Architecture

Architecture, like many other fields, is not immune to bullshit. The concept of bullshit architecture can be traced back to philosopher Harry Frankfurt's famous essay "On Bullshit." According to Frankfurt, bullshit is language that is designed to impress or persuade rather than to convey truth. The rise of bullshit is a symptom of broader cultural trends, such as a decline in respect for truth and expertise, and a greater emphasis on image and perception. Frankfurt suggests that bullshit has become pervasive in many areas of contemporary society, from advertising and politics to academia and the media. In architecture, this can manifest in a variety of ways, such as when architects prioritize trendy aesthetics over function or use jargon to obfuscate their ideas.

To counteract the prevalence of bullshit architecture, we can focus on bringing forms to life and serving the life and beauty on earth. By perceiving space as a continuum and valuing the inherent value and life within it, we can create designs that resonate with authenticity. Incorporating the properties of living systems allows us to craft spaces that are alive, vibrant, and deeply connected to their larger context.

Moreover, architects should communicate their ideas clearly and honestly, avoiding the use of jargon and obfuscating language that only serves to confuse and impress rather than convey genuine meaning. By promoting transparency in their designs, architects can foster a deeper understanding and connection between the built environment and its users.

This rejection of bullshit architecture aligns with the broader cultural shift towards valuing truth and expertise. In a society where image and perception often overshadow substance, architecture has a unique role to play in reestablishing the importance of function, context, and human experience.

By creating spaces that are not only in tune with the natural order but also responsive to the needs and aspirations of the people who inhabit them, architects can shape a built environment that reflects our values and enriches our lives. Through a commitment to craft, integrity, and the pursuit of genuine meaning, architecture can transcend the superficiality of bullshit and contribute to a more thoughtful and living world.

Serious Play

"Play is the means by which we discover the world, and by which we learn to imagine new possibilities." ~ Ian Bogost, Play Anything

Play isn’t about doing whatever you want, it is about doing what you can within restraints. In play, creativity is not a form of self-expression, or a pursuit of freedom, but instead limiting freedoms found in the creation of something new through transforming material constraints in surprising ways. Play is the act of finding creative solutions within constraints. It's a skill that can be learned through practice.

Play is the participation in pattern recognition and opens up possibilities for creative intervention in the outside world. While play offers the capacity to deliver rewards, it’s ultimate purpose is not to bring happiness or pleasure, but rather to induce optimal experience, or flow.

According to James Carse, there are two types of games: finite games and infinite games. Finite games have fixed rules, known players, and agreed upon objectives. The game ends when one beats others and joy comes from comparison. Infinite games, on the other hand, have no fixed rules or outcomes. The goal is to keep playing and the joy comes from advancement. Culture, for example, is not about achieving a particular end or goal, but rather to maintain and build upon what has already been created.

Infinite play is about embracing the present moment and finding joy in the process, rather than focusing on the end result. It's about seeing the world as a place of infinite possibilities and recognizing that there is no final destination. When we approach life as an infinite game, we can let go of the need to control and instead embrace the uncertainty of the future. The artist is not seeking to definite themselves in a finite game, the artist is someone who engages in an ongoing conversation with the past, present, and future, and who seeks to expand themselves and the boundaries of what is possible.

Infinite games are a source of meaning. How can we encounter more play of infinite games in our lives? By recognizing that life is an infinite game, we can let go of the need to win and instead focus on the joy of playing. We can embrace things for what they are, not what they lack, and do what we can with what’s given.

The Art of Architecture

“You never change things by fighting the existing reality. To change something, build a new model that makes the existing model obsolete.” ~ Buckminister Fuller

Art and architecture have always been considered different forms of expression, one driven by emotion and the other by function. Architecture is the process of designing and constructing structures that serve a purpose. I tend to think of it as creating order. Art, however, is the emotional expression of order.

Architecture is not just about creating physical spaces, but is also about shaping social and cultural spaces. A building is an adaptive complex system that can evolve over time, responding to the needs of its inhabitants, providing us with spaces that facilitate our activities and shape our experiences. Architecture is not simply the act of building, it's the process of designing and creating spaces with intention and purpose. However, not all buildings can be considered architecture, only those that respond to the cultural and social needs of the people. Many buildings are merely commodified versions of architecture, stripped of the art and intention behind true architectural design.

While buildings serve functional purposes, architecture is concerned with more than just utility. It is an art form that considers how a structure interacts with the environment, the emotions it evokes, and the meaning it holds. Architecture expresses power and control over the environment. This is unique from art, which is rather can be considered a way of challenging that power and creating new possibilities. Art is more of a momentary expression of human emotion and experience. It is often created without the intention of serving a particular function or purpose, but rather as a way of expressing the self. Art is highly personal. Architecture is social.

Good design is functional, expressive, and based on nature. It should serve a purpose and should be designed to meet the needs of its users. It should communicate something about the people who built it and the time in which it was built. It should be in harmony with its surroundings and should reflect the beauty of nature.

Ultimately, whether we are creating art or architecture, we are engaging in a profound act of expression and shaping the world around us. We are declaring our presence in the world and our desire to make a meaningful contribution to it. Art and architecture offers new ways of seeing and being in the world that can leave us with more questions than answers.

Individual Responsibility and Nonconformity

Responsibility to one’s self is the ultimate responsibility. In a world that often emphasizes collective responsibility and results in conformity, it can be easy to overlook the importance of individual responsibility. Art and architecture offer valuable insights into the significance of personal accountability, discipline, and self-reliance.

The individual is the most important unit of society. Individuals ultimately serve the greater good. By pursuing one's own rational self-interest, individuals can contribute to the advancement of society as a whole. Democracy is based on the idea of individual liberty and the pursuit of happiness, but this freedom also requires individuals to take responsibility for their own lives, which subsequently contributes to the common good. Democracy requires a balance between individualism and collective responsibility.

Similarly, art is about the individual artist, their growth in the creative process, and the collective responsibility in service of art. The artist creates for the sake of the art itself, rather than any external validation or commercial success.

Each person has a responsibility to themselves to live a life of meaning by taking ownership of one's own actions. This idea is particularly relevant in the context of art and creativity, where the individual's unique perspective and vision are essential for producing meaningful work.

Art and architecture offer valuable insights into the significance of personal responsibility, which can be applied to various areas of life, including creativity, personal growth, and societal progress. The individual is not separate from the collective. My hope is to cultivate and inspire a culture of creativity and nonconformity to benefit the collective.

Embracing Ambiguity

‘To see is to forget the name of the thing one sees.’ ~ Paul Valéry

We exist in a constant state of flux, and our understanding of the world is always incomplete. It is this ambiguity that makes life interesting and worth living.

In art, ambiguity is a powerful tool. Rather than reproducing the visible, art makes visible the ambiguous, the uncertain, and the unknown. It challenges our assumptions and invites us to question our understanding of the world. As Paul Klee famously said, "Art does not reproduce the visible; rather it makes visible."

In a society that values clarity and certainty, ambiguity can be unsettling. We often seek to categorize and label things, to neatly fit them into preconceived boxes. But this desire for neatness and order can lead to a narrow, limited view of the world. When we focus too much on labels and categories, we miss the richness and complexity of the world around us.

Embracing ambiguity can be uncomfortable, but it is also liberating. When we acknowledge that our understanding of the world is always incomplete, we open ourselves up to new experiences and new ways of thinking. We become more humble and receptive to the perspectives of others.

The ethics of ambiguity invite us to embrace the unknown and to live with a sense of openness and curiosity. By doing so, we can coexist and flourish together in a world that is inherently uncertain and constantly changing.

The Soul of Architecture: A Journey of Creation

As an architect, I’ve come to realize the heart is generous, the brain is selfish. What does this mean in the context of architecture? The heart yearns to create spaces that connect, that give back to the world, while the mind often falls into the trap of logic and efficiency. Yet, in the pursuit of balance, architecture becomes a screen that can either reveal or hide who we are as people, just as much as it hides the natural world behind structures.

Architecture is more than the sum of its parts. It doesn’t begin with a building or end with a demolition. It lives through the experience of those who interact with it. To me, architecture has no beginning and no end. It’s an infinite creative process—one that’s as subjective as it is objective. Every material choice, every spatial decision, opens up infinite possibilities for interpretation.

Simplicity is key. We don’t need to overcomplicate our designs or our lives. Yet, simplicity is deceptive; it hides the infinite complexity beneath. Great architecture, like great art, is not about showing off complexity, but about discovering the hidden power of simplicity and clarity. As Louis Sullivan said, “Proportion is a result, not a cause”, and I take this to heart in my practice.

What truly drives me is the entrepreneurial spirit—the belief that we have the power to shape our destiny through our work, to express ourselves through built form. Life, like architecture, is instrumental, physical, and mental, constantly in a state of becoming. We are not just designing spaces; we are designing experiences. And the true goal is to evoke feelings—whether joy, peace, or even terror. Because without terror, we cannot truly appreciate beauty.

Architecture should not be seen as a discipline of words or abstract ideas, but rather as a form-making practice. At its core, it is about creating meaningful spaces. Spaces that are connected to the environment, shaped by nature and materials, guided by ethical simplicity.

But simplicity does not mean plainness. Architecture can—and should—be both eclectic and esoteric. It carries with it an infinite chain of signifiers, referencing not just other buildings, but our past, our experiences, and our culture. The ornament is not a decorative afterthought; it is a signifier, a reference to something deeper. In my designs, I aim to capture that—using the index of material and form to evoke emotion and connect people to their surroundings.

Ultimately, thought is superior to the senses, and intuition superior to observation. Great architecture reveals itself not in how it looks, but in how it feels and functions in the world. The voids, the negative spaces, are just as important as the solid forms. This void distinguishes the nature of things, allowing the architecture to breathe and resonate with the lives of those who inhabit it.

In the end, architecture is a practice. Love is the highest teaching, and I believe that in both life and architecture, we live in love. Whether designing a home, a community space, or a city, it’s this love that sustains us and keeps us connected to the world and each other.

Energy

“Form is a force, not a static object” - Christopher Alexander

Energy is one of the most critical economic and social issues of our time. The discourse has primarily centered around energy conservation as a strategy to address environmental impacts. However, architecture and design have the potential to revolutionize the energy landscape. A sustainable future can be achieved by transitioning from centralized, fossil fuel-based energy systems to decentralized renewable energy sources. To bring this aspiration to life, smart microgrids that integrate renewable energy generation, energy storage, and distribution networks are essential. These systems enable individuals and communities to become energy producers and share their surplus energy with others.

Architecture and design are not just physical objects but are dynamic forces that constantly evolve and adapt to the people and communities they serve. When it comes to energy, the form of our buildings and cities plays a significant role in our energy consumption. Buildings account for roughly 40% of global energy consumption and carbon emissions. But what if buildings could be designed to generate energy?

This is where the concept of energy-positive buildings and Passive House comes in. Energy-positive buildings generate more energy than they consume, which can then be fed back into the grid. These buildings are designed to harness renewable energy sources like solar power and use energy-efficient strategies to reduce energy consumption. This is a prime example of how injecting energy into a building in the form of renewable energy sources can turn it into a dynamic force, generating energy for the wider community.

The same can be said for proof-of-work systems like Bitcoin. Proof-of-work involves solving complex cryptographic puzzles to validate transactions on the network, which requires significant amounts of computational power and energy. Critics of proof-of-work argue that this energy consumption is wasteful and unsustainable. However, supporters of proof-of-work argue that this energy consumption is necessary to secure the network and prevent centralized malicious actors from taking over.

In a way, proof-of-work systems inject energy into the network, turning it into a dynamic force that is constantly evolving and adapting to the changing needs of the community. Overall, the concept of proof-of-work highlights the idea that significant effort and energy is required to achieve a certain goal, whether that be validating transactions on a blockchain, creating a well-crafted, energy positive building. In terms of craft in buildings, the concept of proof-of-work can be seen in the attention to detail and quality of craftsmanship in a building project. Just as miners need to put in significant effort and energy to solve complex puzzles in proof-of-work, craftsmen need to put in significant effort and skill to create a well-crafted building.

The concept of energy-positive buildings highlights the potential of injecting energy into the built environment to create dynamic, self-sustaining systems. Similarly, proof-of-work systems like Bitcoin inject energy into the network to ensure its security and stability, turning it into a dynamic force that is constantly evolving and adapting to the changing needs of the community. As we continue to grapple with issues like energy consumption and sustainability, it is essential to embrace this dynamic approach to design and technology and harness the power of energy to create a more connected world.

Fiat architecture lacks a connection to reality and truth. The term "fiat" is often used to refer to something that has been established or created by authority or decree, rather than being based on consensus or quality. For example, fiat currency is paper money that has been declared legal tender by a government, even though it is not backed by a physical commodity like gold. In the context of architecture, fiat architecture can refers to buildings and spaces that have been designed primarily for image or status, rather than for functional or aesthetic reasons. Another way to approach architecture that is rooted in reality and truth is to consider the value of human labor and craft, a concept that John Ruskin explored in his work. Ruskin believed that architecture should reflect the values of society and the skills of the craftspeople who built it, rather than simply serving as a symbol of wealth and power.

This idea is similar to the concept of proof of work in Bitcoin, where the value of the cryptocurrency is tied to the effort and energy expended by miners to validate transactions. Like Ruskin's emphasis on the value of labor, proof of work emphasizes the importance of effort and work in creating something of value. In a world where our built environment and financial systems are becoming more dynamic and self-sustaining, it's clear that the old models of centralization and uniformity are no longer enough. Instead, we must embrace the power of energy and the organic, living systems that it can create. From energy-positive buildings to proof-of-work systems like Bitcoin, the future belongs to those who can harness the power of energy and use it to create more dynamic, adaptable, and sustainable systems.

Bringing Forms to Life

“Life, the universal power, or energy which flows everywhere at all times, in all places, seeking expression in form….” ~ Louis Sullivan

“It is possible to paint a living thing.” - Philip Guston

How can we greater serve the life and beauty on earth?

Over time, space can be given value by adding beauty. This continuum does not have strict borders, but approximate and adaptive boundary zones and centers.

Bringing forms to life is one of the primary functions of art and architecture. As opposed to Cartesian space, value and life are inherent to space. The universe is not a collection of separate objects, but rather a continuous whole, and this wholeness can be perceived through our sense of life. When creating (ie. a drawing) it is conceivable that every added agent (ie. line) can increase or decrease that form’s life. Good design makes one feel more connected to that space and connects to its greater context. The higher the degree of connection, the greater the Life. As the life form develops and grows with its environment, its Nature changes over time. A living work is a window to what is True.

Art should not merely be pleasant or interesting, but it should be contribution to the spiritual condition of the world. We should strive to make others more related to the universe and the truth of creativity.

The architect and theorist Christopher Alexander expands upon this notion more in depth in the four volumes of the ‘Nature of Order’ where he describes 15 properties of living systems. These properties are based on the observation of natural forms and the way they grow and evolve over time. In his work, Alexander explains that every living form is made up of smaller, living parts. By incorporating these properties into our designs, we can create spaces and works of art that are alive and vibrant. Each property has a unique contribution to the aliveness of a system, and together they create a sense of wholeness and connection to the larger context.

Through a deep understanding of these properties, we can create spaces and works of art that are not only beautiful but also serve the greater purpose of contributing to the aliveness of the world. It is through the integration of these properties that we can better serve the life and beauty on earth.

Strategy without Design

“Strategy without design is about making room, the limits of which are not boundaries, but the edges where things begin their essential unfolding. Strategy without design is building for the dwelling of things, notably our self amidst other selves and other things. This is what it is to practice the art of the general: not to cover and control life from above, but to bring forth things by cultivating the things that grow, and constructing the things that do not.” ~ Strategy Without Design: The Silent Efficacy of Indirect Action

Design and strategy are often seen as separate entities, with design focused on aesthetics and functionality and strategy focused on planning and execution. However, this separation can be problematic as it fails to recognize the interdependence of these two fields. Design provides a framework for strategy to operate within, and strategy gives direction and purpose to design.

When we think about strategy and design, we can also consider the concept of open and closed systems. Closed systems aim to control and manage everything within their boundaries, while open systems allow for a certain degree of flexibility and adaptability.

In the realm of economics, free markets are an example of an open system, while centralized systems are closed systems. The beauty of a free market is that it allows for individual actors to pursue their own self-interests, which results in the creation of a diverse range of goods and services. This decentralized approach allows for a constant flow of innovation, with businesses and individuals competing to provide the best possible products and services.

On the other hand, a centralized system seeks to control and manage everything, which can stifle innovation and creativity. While it may seem efficient in the short term, a centralized system often lacks the adaptability and resilience to handle unexpected events or changes in the environment.

Open systems allow for a more dynamic and adaptable approach to economics and beyond. Closed systems may appear to be more efficient, but they lack the flexibility to respond to unexpected changes. Open-endedness is crucial for the coexistence and flourishing of diversity. By embracing open systems, we allow for the free flow of ideas, resources, and opportunities, fostering creativity and innovation. Closed systems, on the other hand, limit the potential for growth, innovation, and adaptation.

In a rapidly changing world, it is more important than ever to embrace open-endedness and avoid rigid, closed systems. Open systems, such as free markets, allow for a diversity of ideas and perspectives to flourish, creating a more resilient and adaptive society. By embracing open-endedness, we can build a more interconnected and dynamic world, one that is better equipped to address the challenges of the future.

Today, much of the environment is designed to say ‘everything is ok’, and society’s perception of the world remains unaffected. The trend of reducing risk and increasing efficiency has also resulted in the decline of imagination and intuition as a human condition. For this reason, Architecture should do less of trying to predict how users will interact with a space, but rather produce offerings or fragments of what might make sense and challenge the viewers to interpret or question its meaning. Architects should not produce a definite final object, but can rather create something open and incomplete as a way to inject spontaneity and unpredictability into the world.

Pecha Kucha

Moving a lot when I was younger taught me to welcome new experiences as a source of play and adventure. This is a sketch I made of Don Quixote, one of my favorite books. What I appreciate is that he sees the world the way he believes it to be, no one tells him otherwise. Don Quixote got seemingly delusions because he read too many stories.

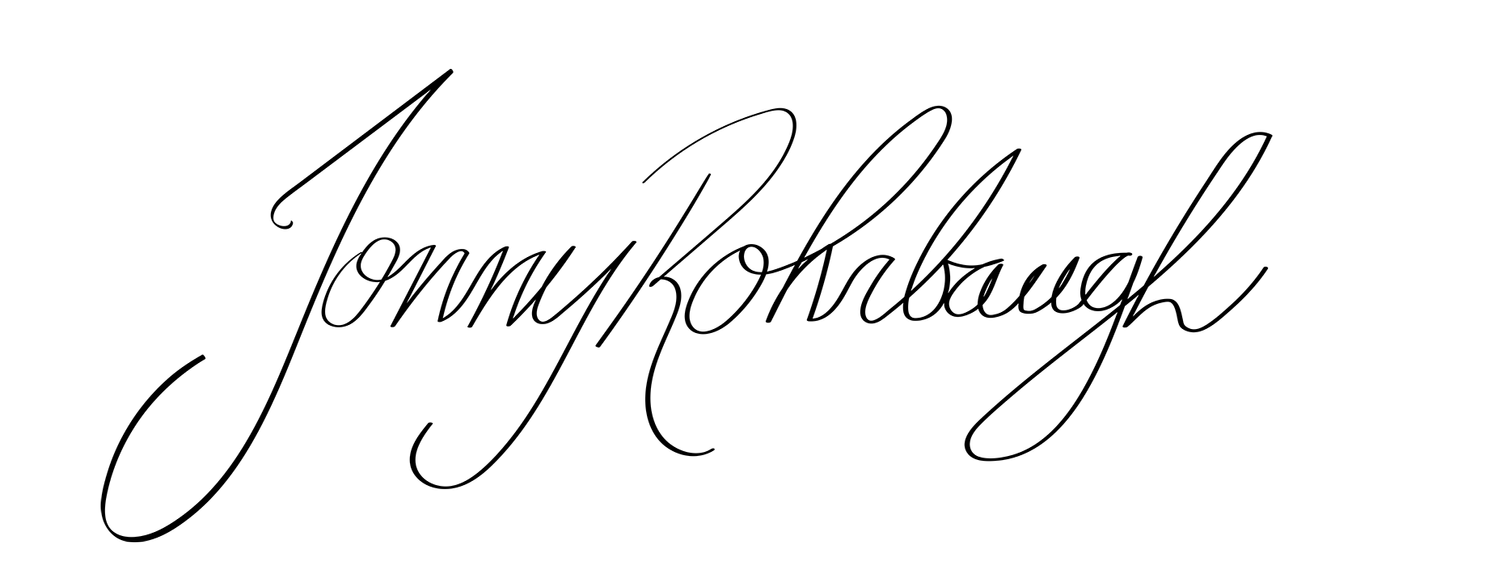

I also find myself creating my own stories, not as a way to explain the world, but to describe new ways of seeing. Books and stories play a large role in my life because I believe stories are where we find meaning. So much so that my graduate architecture school thesis became a fiction story, here is a drawing from that, in which I researched architectural ornamentation.

I believe that humans have a biological or evolutionary predisposition for ornamentation. Historically, ornament has always appealed to nature whether by applying laws of nature or attempting to imitate it. Ornamentation can promote pattern-forming abilities that help increase awareness of connectedness.

In 2014, I began a practice drawing experimentally at different scales, without a predictable outcome, using nature based rules in an attempt to construct spatial relations that respond to local conditions. I became more interested in the process of how forms emerge, more than what they resulted to be. The drawings self-organize as a complex adaptive system.

The drawings are like a freestyle. Hip-hop music, along with reading, have been two modes of cultural production that influence me most. This is a concert hall from an adaptive reuse school project. A hip-hop architecture not about creating a ‘machine’, but setting a stage. By considering participation, architecture can encourage others to transform their own space.

Whether artificial or natural, form is generated through a stepwise process. I see architecture more as a set of relations than being reducible to an object. This architecture from my time at SCI-Arc considers how forms are capable of being generated using software, and what potential applications technology can provide.

One of my most rewarding projects was a culmination of a powerful story and digital fabrication during my time as a Branded Environments Designer at Perkins+Will. This History Wall at Austin Community College reflects the story of an African American congregation that established an orphanage on the site before it became a Mall in the 70’s.

Being a Branded Environments designer was a way for me to continue my pursuit in ornamentation in today’s world as a way to express identity with coherence and purpose. From the small scale bats emerging as a suspended sculpture, to a logo in the trellis and entry sign, to scaling up even larger for the parking garage signage visible from the freeway.

Here on the Dallas Cowboys Frisco campus, the lobby of the Sports Therapy and Research Center offered a 3 story entry space. The suspended sculpture captures movement of users walking into the space through reflective panels. Upon entering the lobby, the colored pieces are revealed to form the logo when looking up.

It’s important to me to consider the human hand and craft in buildings. This interdisciplinary approach towards the flower wall was a means of orientation, not only within the building, but also in the cultural context. By introducing an element of play, we can encourage the participation in pattern recognition and open up possibilities for creative intervention.

Too much of our world today is designed to say ‘everything is ok’. Reducing risk and increasing efficiency has also resulted in the decline of imagination. I challenge the fact that architects should produce a definite final object, but can rather something open and incomplete as a way to inject spontaneity and unpredictability into the world.

‘Floating World’ was a pop-up art exhibition in 2018 in Chicago. The intention of the work was not to define the world, but rather experience new ways of seeing. It presented a series offering that challenges the viewers to question its meanings. The work in this show promotes beauty in the mundane and a search for being a part of something bigger.

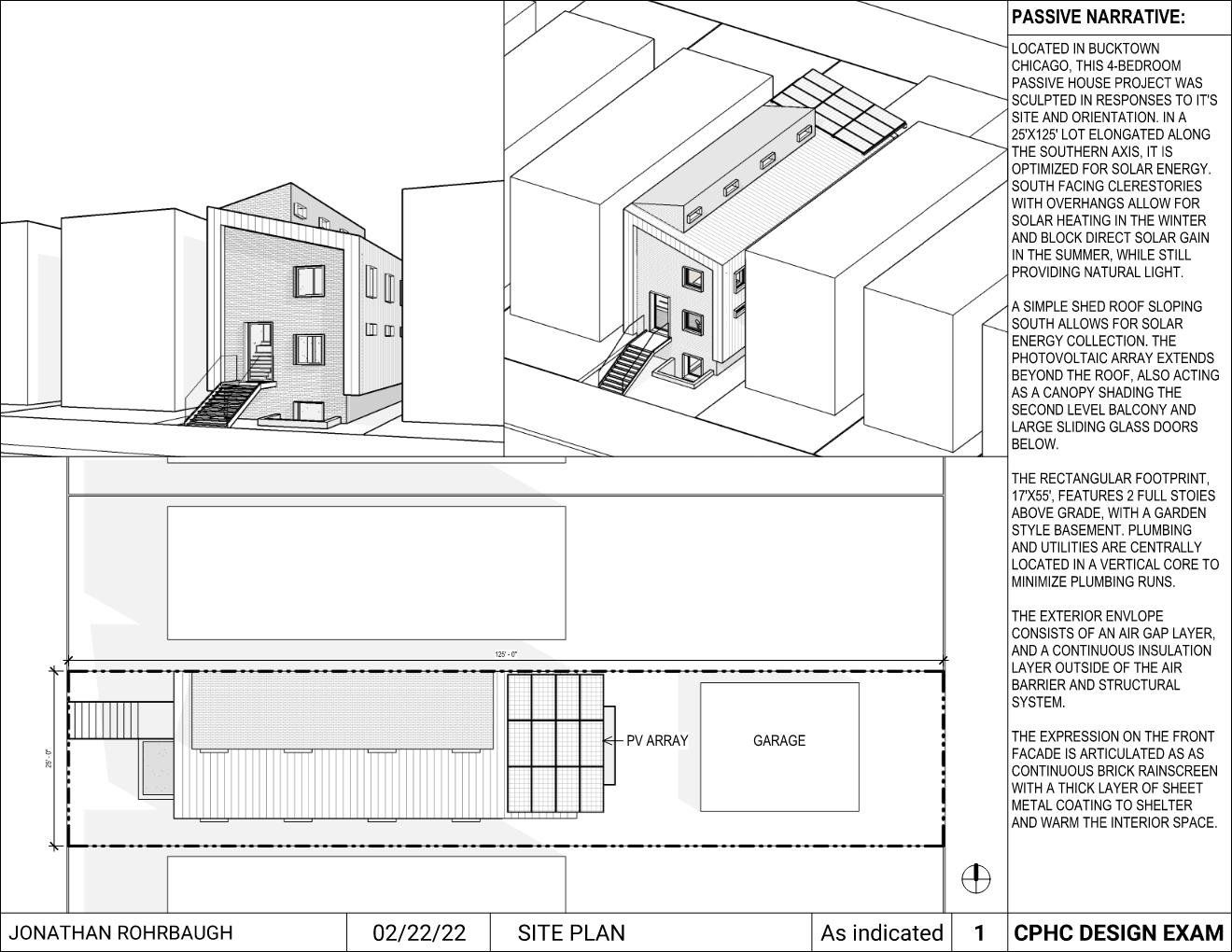

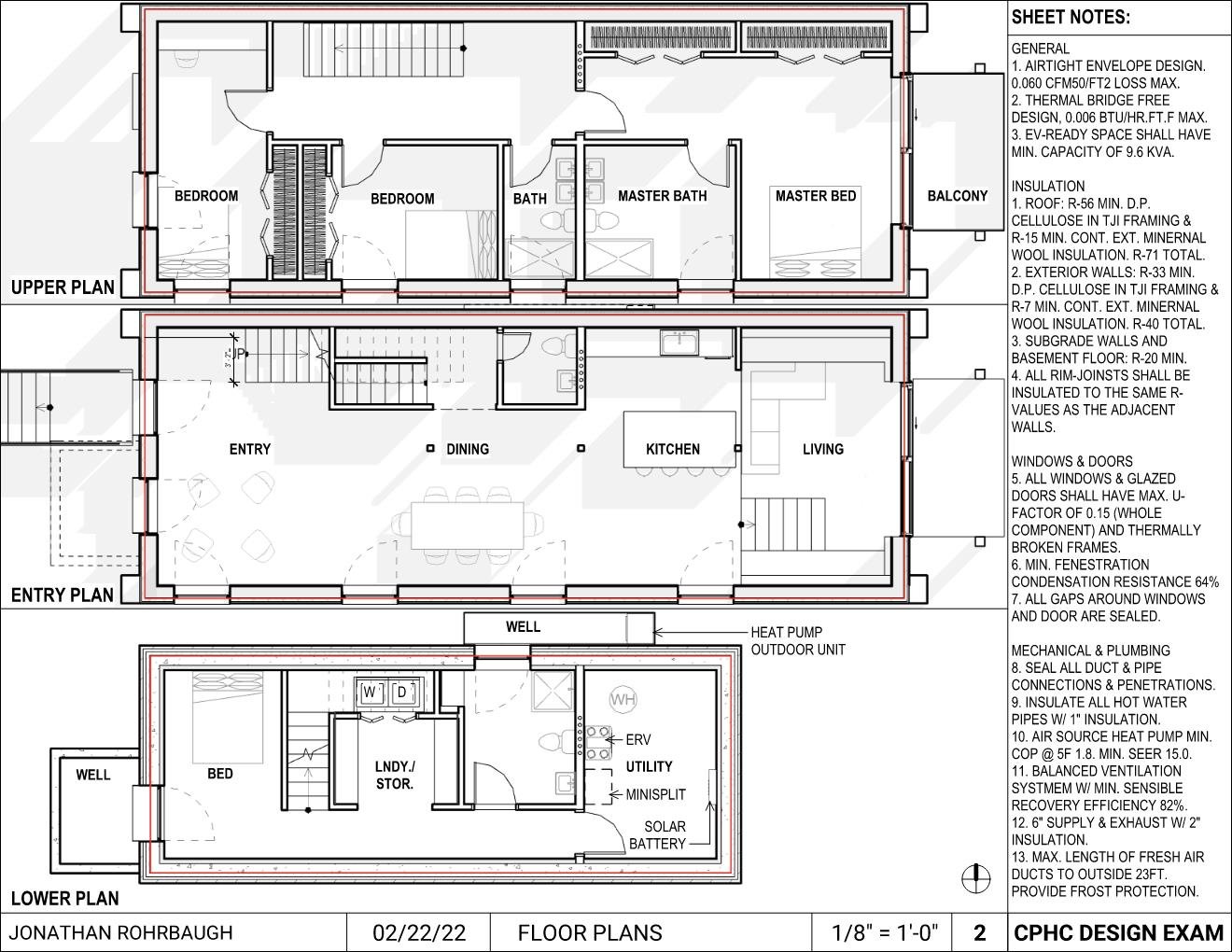

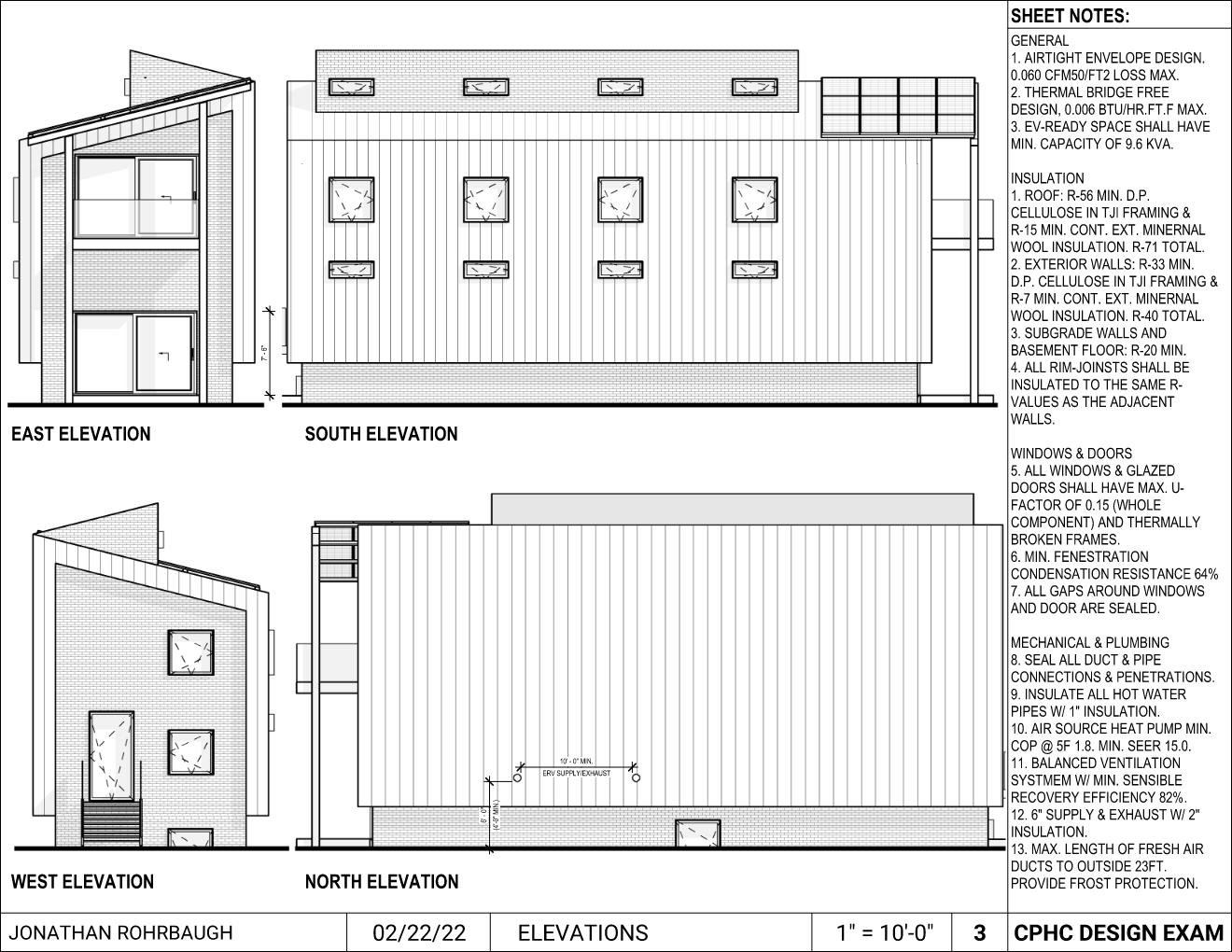

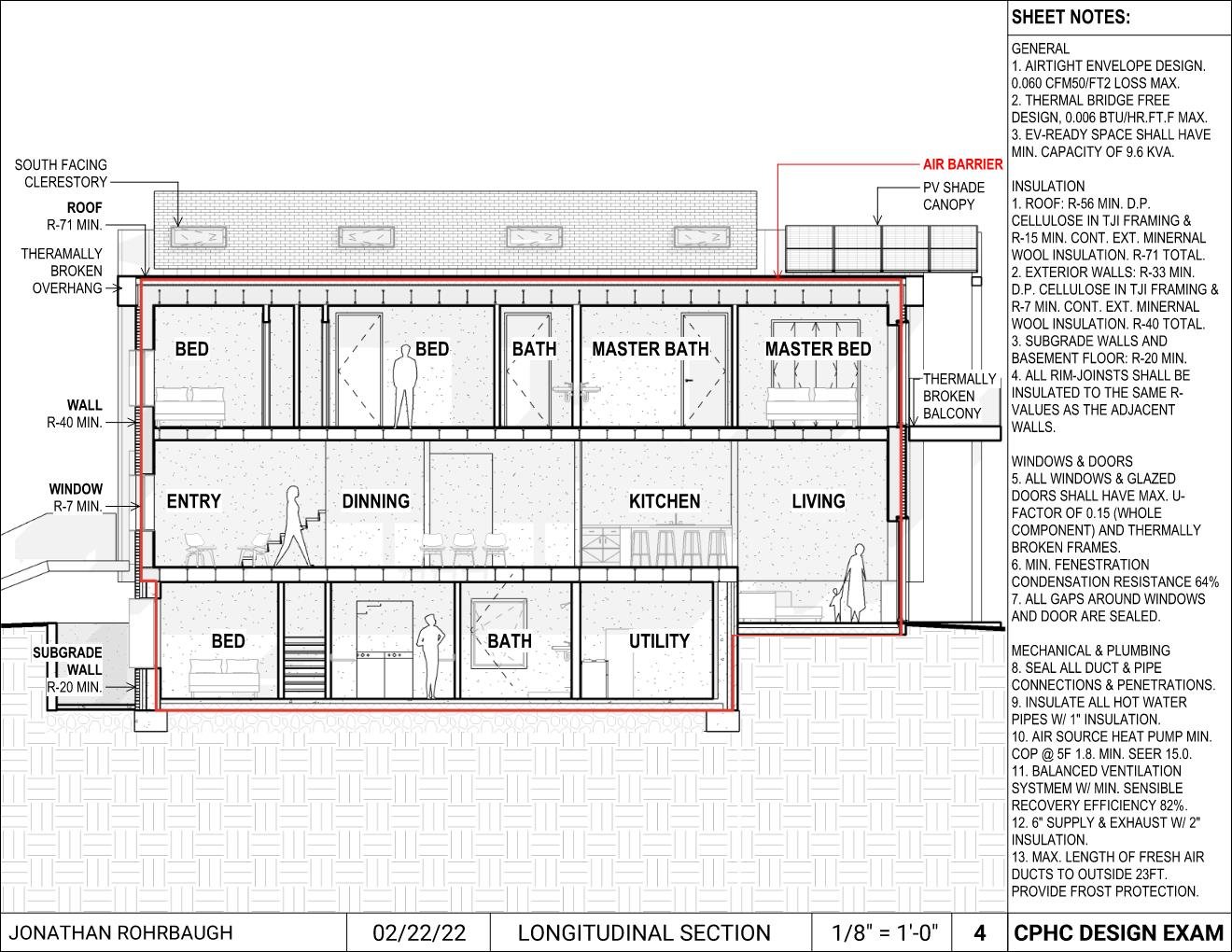

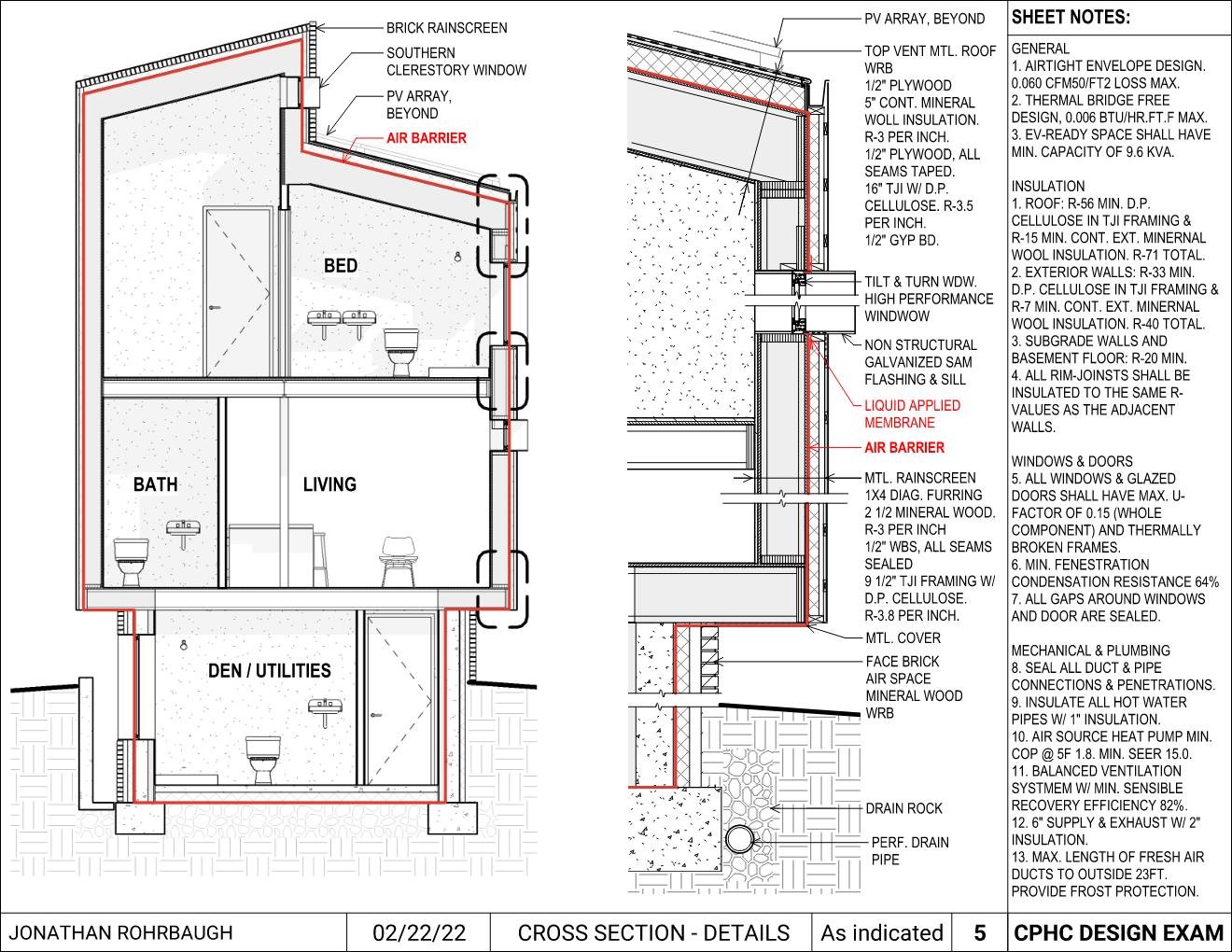

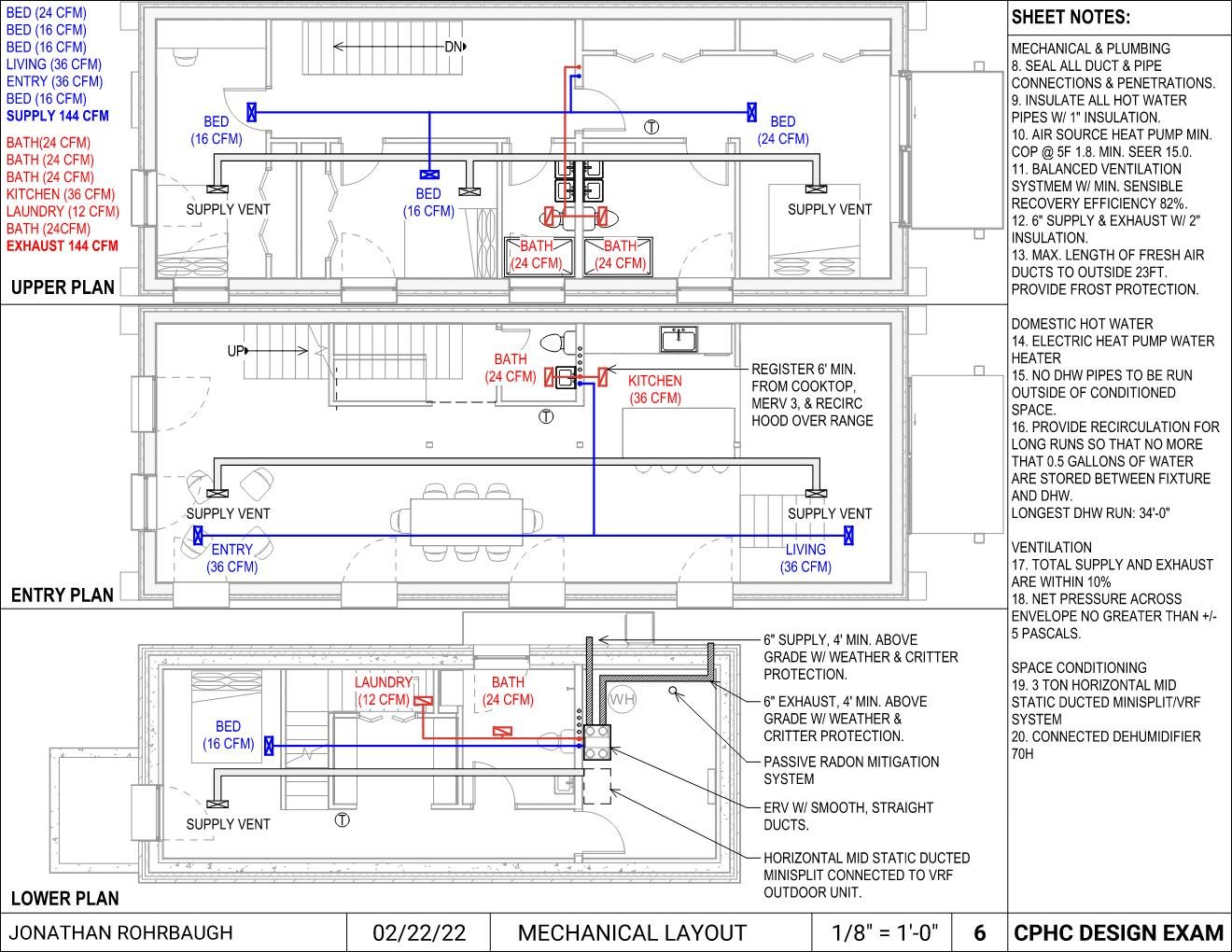

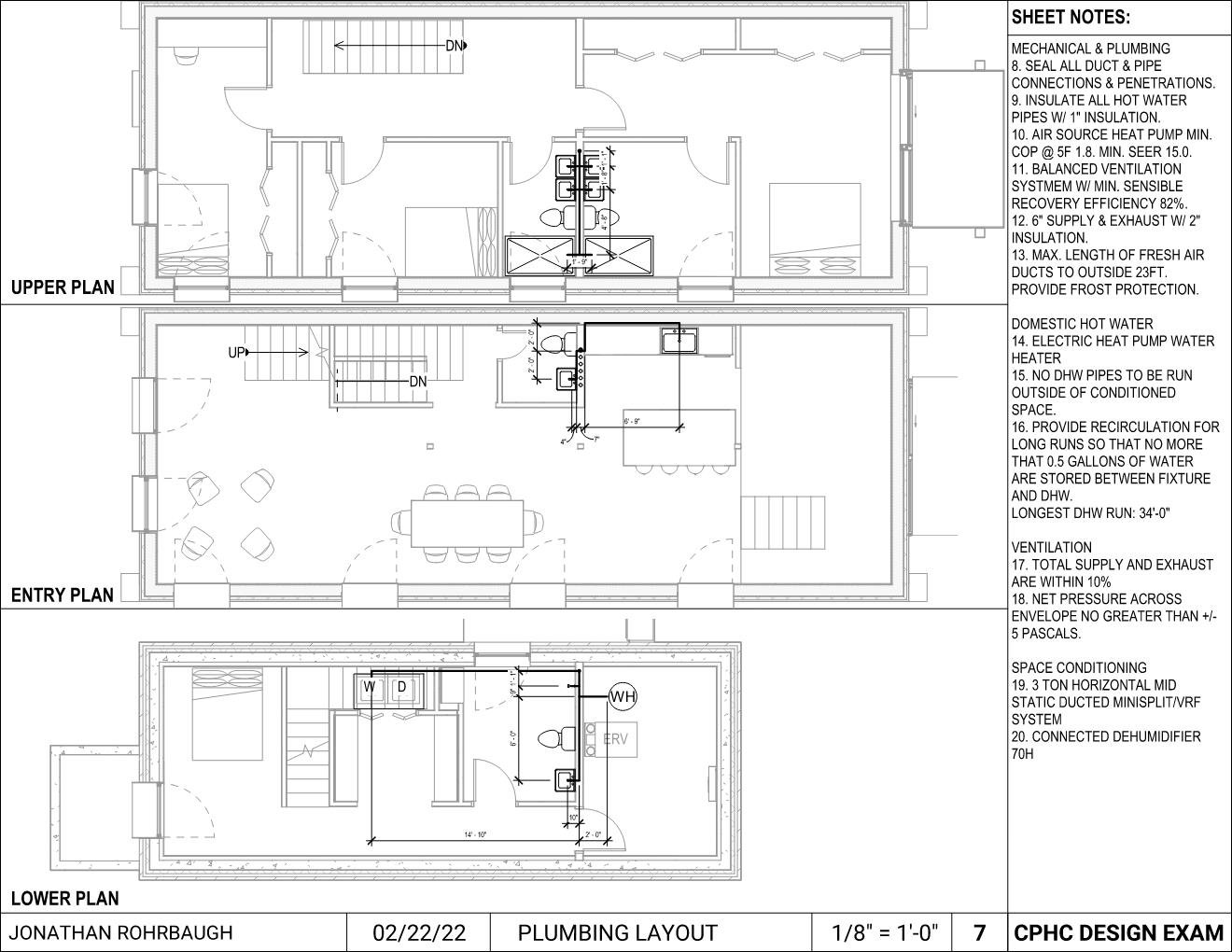

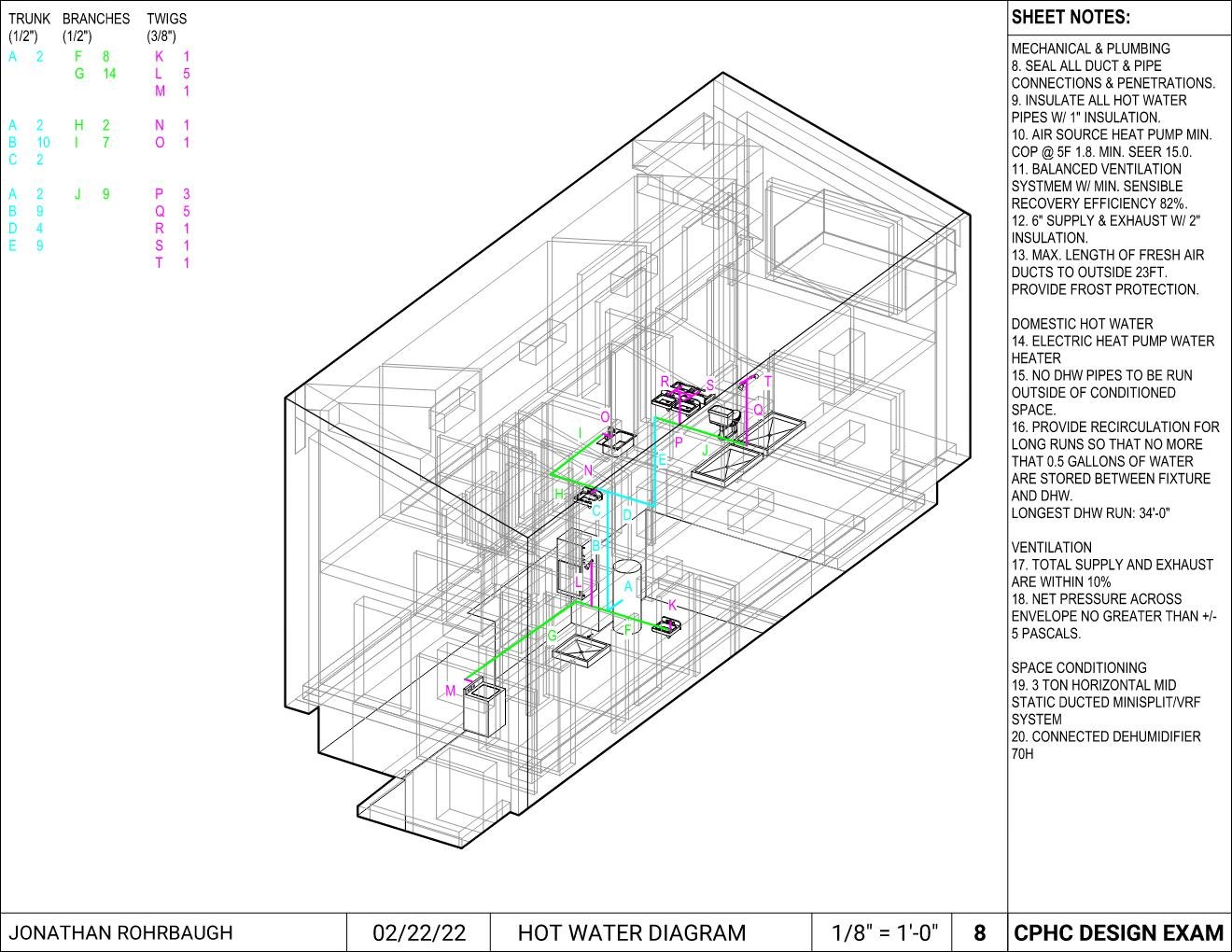

While I believe in individuality, I am dedicated to making resilient buildings as a Certified Passive House Consultant. Ultimately, I am seeking an aesthetic that can emerge from the integration of graphics, sculpture, and sustainable architecture. For my certification design exam, a thick blanket is expressed wrapping over the minimally sculptured roof to maximize solar collection.

The Mendocino House was the first project I worked on at Jensen Architects (here still under construction) and is a Net Zero ready residence in Ukiah. The project is a resilient response to hot summers and freezing winters. The collaborative design/build approach enabled several custom details, including the custom window wall fabricated by the owner.

While landscape is not the only context architectural form needs to respond to, I believe the integration of the two can strengthen each other. This was a project I worked on while at Interstice Architects, who is the landscape architect on a few of our projects. Here, the simple architectural design takes a back seat, while in harmony with landscape.

Here is another example of aesthetics that is not applied, but emerges from a process. Alex, a trained interior designer, and I met in Chicago and recently married this past August. She continues to inspire me on my own creative journey and without her I wouldn’t be here today.

Patterns of Harmony: Scale and Freedom

“The form is a part of the world over which we have control, and which we decide to shape while leaving the rest of the world as it is. The context is that part of the world which puts demands on this form; anything in the world that makes demands of the form is context.” ~ Notes on the Synthesis of Form, Christopher Alexander.

How can we grow patterns to better harmonize people and the planet?

By strengthening local conditions, we can greater strengthen the whole. Every forms’ wholeness is dependent on its surrounding environment. At every scale, there can be more or less life added, or subtracted, and the whole can be made coherent and connected with purpose.

Self-organization is needed in complex systems for emergent responses to unpredictable changing external conditions. Distributed nodes are adaptive and more resilient compared to large centralized ones that are more fragile. Without a single point of control, the whole takes on a life of its own. The efficiency of the system does not depend on a preplanned strategy, but rather emerges from the continuous adaptations to local conditions.

“Since not all the variables are equally strongly connected, there will always be subsystems like those circled below, which can, in principle, operate fairly independently. ~ Notes on the Synthesis of Form, Christopher Alexander.

Hierarchical subdivision are necessary for a scaling coherence. Interconnected networks or objects that are distributed across time and space can establish more or less order at each scale. The growth of systems are the result of a morphological, step-wise process that is capable of adapting more or less to its environment at each stage of development. While models can be helpful, the element of freedom introduced unpredictability at multiple scale.

Freedom is not something given, but rather a form of resistance. It is commonly assumed that we are born free, but did we choose where and when to be be born? We experience freedom when we take it upon ourselves to take action and not conform to someone else’s ideas.

Freedom at the smaller or ornamental scale reinforces creativity of the whole.

Life moves towards greater freedom.

“What irrelevant at one scale becomes dominant at another.” - Geoffrey West, Scale.

Becoming a Certified Passive House Consultant

Why Passive House?

As an architect, I’m interested in how my work can lead to a path of zero-carbon building, and we know that carbon emissions from building operations are a substantial contributor. Passive House focuses narrowly on the building envelope as the critical component for achieving zero-net-energy performance. I appreciate its scientific basis; becoming a CPHC gives me the ability to do the actual modeling. But it’s the interplay of airtightness and thermal bridging, all the ways heat can escape or enter a building, and the architectural form that emerges from these considerations that really interests me. As a result, Passive House standards deliver a more durable and resilient building.

What is the path to expanding the industry’s use of Passive House?

Widespread adoption of Passive House standards is within our reach in California, where we have strict energy codes and a temperate climate. Also, in 2021, the Passive House Institute US adopted a more prescriptive method for single-family homes, which further lowers the barriers to entry. So, it’s really a matter of helping clients understand that it’s an investment with a lot of benefits, and not an extravagant, unachievable standard. The cost delta for Passive House isn’t major when weighed against the benefits: minimizing carbon output while providing people with a building that’s quieter, thermally comfortable, supplied with filtered air, and supported by renewable energy.

Your practice has always incorporated painting and sculpture. How do you reconcile these interests with the more scientific grounding of Passive House?

There really isn’t anything to reconcile. Passive House as a measurable framework is part of a set of aesthetic considerations. What aesthetics emerge from these super insulated buildings? The thick roof and wall assemblies are something to celebrate, not hide. The Mendocino House, though not pursuing PH certification, illustrates this idea. An urban example is my design proposal for a four-bedroom Passive House in Chicago, which was optimized for solar collection and expresses the continuity of a thick layer of insulation that wraps from wall to roof. Its south-facing clerestory aesthetically peaks through the thick blanket to allow natural light deeper into the space for solar gain. On a larger scale, as with Net Zero Library Competition, these strategies for net-zero building and resiliency take on greater creative dimensions.

What advice would you offer to someone considering becoming a CPHC?

Anyone considering becoming a CPHC can visit phius.org to learn more about the process and the steps to certify projects. I would recommend checking out some of the free Passive House content on YouTube posted by Passive House Accelerator, PHIUS, and others. Lastly, stay focused on the goal of zero-carbon building – Passive House is the necessary first step in maximizing energy efficiency in buildings. We also need to minimize embodied carbon and electrify our buildings with renewable energy. Consider what aesthetics can emerge through this integrated approach.

Hip-Hop Architecture

When hip-hop emerged from the urban renewal in the South Bronx in the 1970’s, the slums in a post-industrialized city experienced residential depopulation and became a space for expression. Schools, parks, and subway cars became performative spaces for rappers, dancers, and graffiti artists. It was originally a vernacular practice. Reappropriation considers working with what’s available and transforming it into a wider aesthetic. As a result, an under-capitalized aesthetic program developed within mainstream consumer culture and encourages a new counter culture. Now that hip-hop has become a mass culture, commercialized, and imposes a form of self-definition. Yet, “A revolution that does not produce a new space has not realized its full potential”. This is the duty of the hip-hop architecture.

Hip-hop architecture must also express struggle; the struggle from power from powerlessness, whether psychologically or materially. Hip-hop is not about nourishing agents already in power, but rather encourages others to create change in their own way, and to make contributions to the world. Hip-hop of this fashion is not about entertainment, although that may be a resulting affect; the goal is to invest more consciousness in communication and meaning. The goal of this architecture is to catalyze an appropriate distribution of power. The way to do this is by evoking design as being ‘politically incorrect’ as a way of endangering the hierarchy and heterarchy by disrupting the legibility of social structure. Alejandro Zaera Polo argues, “rather than rejecting the political in architecture, the attack on political correctness is an attempt to avoid architecture becoming simply a vehicle for political representation to become instead a viable political instrument”. The result of hip-hop architecture is not in form/style, but rather a state of mind (the entrepreneurial spirit, transformation, mash-up, remix, freestyling, etc). Most importantly, hip-hop space is not about creating architecture as a ‘machine’, but rather setting a stage. By considering the relation of body and stage through identity, architecture can be an instrument of cultural production that establishes social and spatial consciousness that encourages others to creatively consider transformation of that space.

The Wandering Blind Man

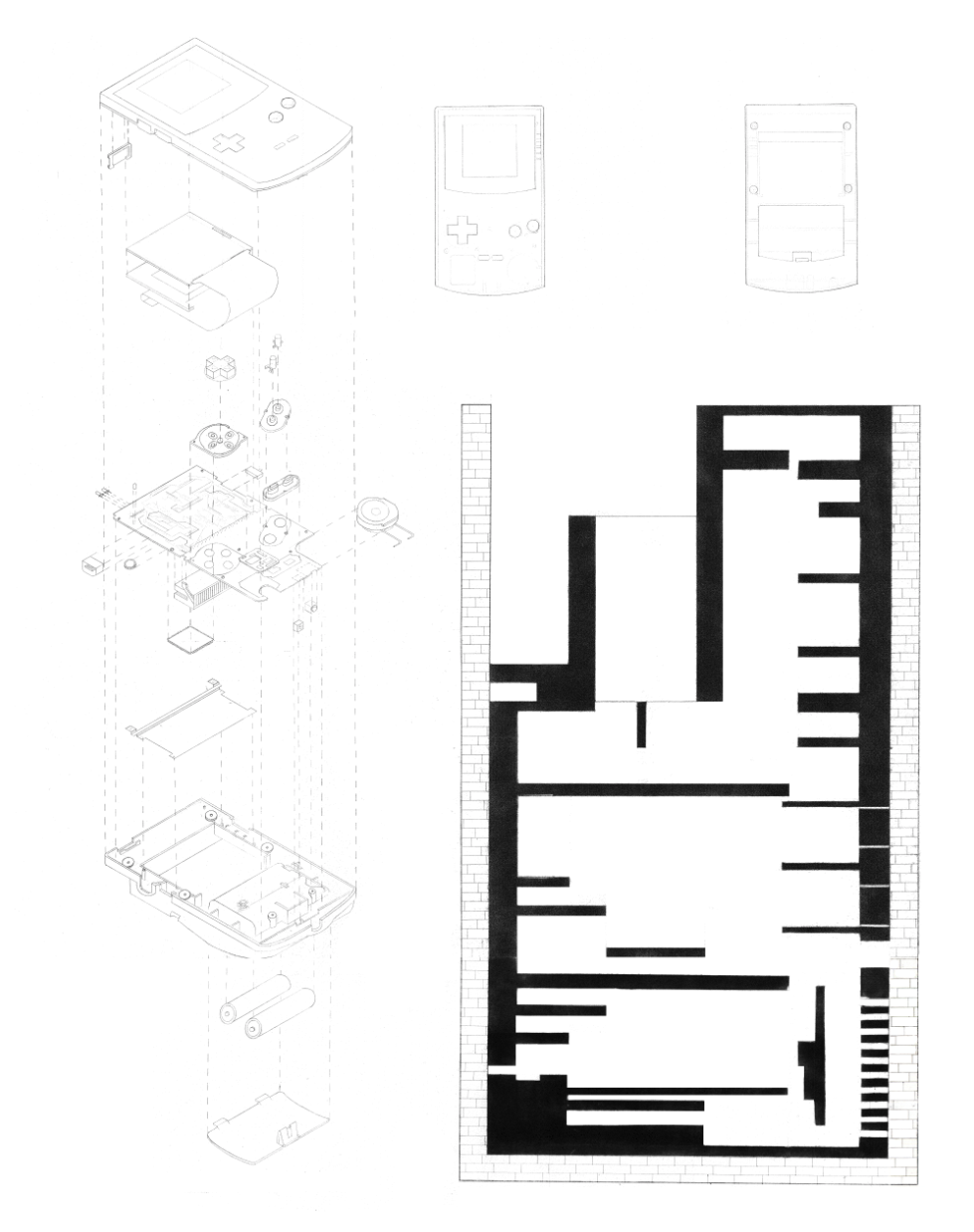

And so the story of Agapios begins... a blind man living in 256 A.D. Chalcis, Greece discovers sight through traveling. Experiencing foreign environments and meeting unique creatures, he identifies the presence of new codes, and discovers a universal language. His travels end at the top of a mountain above An Imperfect City, which pushes him to accept contradiction and embrace the beauty of incompleteness.

Characters

Agapios: Protagonist. Blind man who studies geometry.

Czer: Cyclopes. Ability to disappear into bulk.

The poet: Irrational. Lives in a dream world. Does not believe in the power of knowledge, only experience. Lives without memory, only passion. Every morning is a new morning—a new dream. Lover of the moment.

The painter: Time-deaf. Unable to speak in words. Not concerned with sequence as much as image. Every image is a self-portrait. Lover of reality.

The musician: Looses himself through music. Seeks flow in all actions. Lover of rhythm.

The craftsman: Takes one small step at a time. One good thing becomes another good thing. Lover of making.

The architect: The artist connecting space and time. Lover of structure.

The philosopher: Indifferent to experience. Lover of wisdom.

Man in suit: Rational. Concerned with mass production. Lover of reason.

256 A.D. Chalcis, Greece.

Agapios is a blind man who spends most days wandering. He enjoys studying numbers and geometry. He uses his walking stick to draw lines in the sand connecting stones he has counted. Since he is not concerned with the way things look, he always thinks about the way Nature works. Agapios finds great pleasure in discovering logics and patterns.

One day, he was digging into the earth to study the relationship between the temperature of the sand and the distance to the surface. As Agapios was reaching into the hole he noticed his hand was being pulled until he falls and his whole body spirals down into the earth.

Agapios did not know it at the time, but he was traveling on a gravitational wave—a ripple in space-time. He was transported to a different dimension. Images flashed before his eyes, almost past the speed of experience. He could not make sense of what he was seeing but there seemed to be fragments of logic.

1. Perception

Agapios enters a new environment standing on top of a stony plateau overlooking immense white space. He could see all sides of things. Agapios noticed he was alone with no other creatures around him. Strangest of all, Agapios cannot reconcile if what he is looking at is a building the size of a stick, two steps away, or whether he is looking at a building the size of a mountain in the distance. Either the sizes of objects depend on location or his sense of depth expands and contracts as he moves.

Agapios walks up four steps and realizes the building isn’t so strange. Although he does not know the materials used to construct it, there is rationale in the sequence of construction and fitting of each member. The connections are articulated and aligned. No piece wasted or mandatory—everything is essential.

The walls bend in and out, forming a rhythmic surface extruded and extended across five-foot spaces spanning the facade. On the inside, there is a space that is shaded with tent-like fabric.

Agapios sees a single point in the distance. This point is a compactified dimension—a tiny rolled up dimension that loops back on itself. As Agapios studies closer, he realized this tiny rolled up dimension was everywhere! Countless tiny dimensions—surely one of them would lead him someplace else…

Agapios was not always blind—he lost vision suddenly one morning. Since then, Agapios accepted that mysteries are to remain unsolved and is comfortable with the unknown. He lives on believing in the embedded knowledge of mass—a presence of measurement and materiality—which transcends the divine. He does not have faith, but is consumed by constantly interpreting what surroundings him. Agapios does not learn from his new environment, but becomes a part of it. Although he is unsure of what is beautiful, his constant interest is sufficient to keep him moving.

2. Inspiration

After walking for days on the tiny flat circular dimensions, the density of the circles begins to vary in elevation, slowly building in height. He envisions lines between the shortest segments that will allow him to get to the highest point. He studies their arrangements and is amazed that there is no overlap. Between the circles below, there is nothing but endless space. He is on a thin floating plane.

Agapios encounters his first inhabitant, resembling a Cyclopes. It introduces itself as Czer.

“Welcome,” it says.

“Hello,” Agapios responds, without questioning how Czer could speak his language. “I am amazed by the accuracies of these circles. Can you explain how this plane of circles was first created?”

“Well, my friend, if you knew all of the answers, it wouldn’t be as exciting. I will tell you, though, that this floor is the basis for the entirety of this construction. All forms emerge out of this idea.”

Agapios then pointed to the oval shape tent ahead and said, “This quonset hut does not look like a circle.”

Czer responded without hesitation, “A circle can be an oval, it just depends on one’s perception. Also, and most importantly, the circle inspired it. I do not know where you traveled from, but here all forms are inspired by their unique situation.”

Agapios was half listening as he admired the rippling effects created by the flowing surfaces.

Gazing out toward the plane of packed circles, Agapios noticed he was standing near the edge of a cliff. The fluid that streamed below was the most saturated blue he had ever seen. The coast was built up of thousands of packed spheres, only touching at their tangents. Agapoios appreciated the relatedness amongst the elements in this ecosystem. Czer explained that the boundary adapts to each added circle; like sand on a beach, its shape is transformed overtime in response to the circle that was last added. The change is never-ending.

In this reality, Agapios discerned there are no schedules when the circles are added. He imagines if all events were triggered by other events, schedules would not exist. There are no appointments, no calendars, and no planning. Time is not something measured but a quality defined by the way one follows another.

Czer left Agapios saying, “the time it takes to build is never predictable because its existence is unpredictable. All will transform as soon as I leave.” Czer walked straight off of the cliff, but did not fall. He continued to walk as if in mid air. Like a mirage in the desert, Czer began to evaporate into the flowing waves. The environment, again, was also morphing around him.

Agapios’ body adjusts to the local conditions of space and time because each environment is its own local phenomenon. The closer two environments are, the more similar they seem. Time flows at different rates relative to eachother. Accordingly, scale becomes relative in space and time. This, however, does not account for adjustments to language. He wonders how he was able to communicate with Czer and if he will be able to understand the new creatures to come...

3. Generation

Czer is gone and Agapios is immersed in a growing context. Agapios seems to be in the middle of a village. What appears at first to be underwater, Agapios notices that all of the forms are reaching upwards. They are soft and organic, like biological systems on Earth—interconnected networks, diversity, redundancy, all that seems to self-adapt. Cells, leaves, and branches grow endlessly from the ecological pressures of the site. Moments of growth and decay lead Agapios to believe every piece is alive. Focusing on one detail, he imagines the effects of time. He imagines that in a year, that ornament the size of his fingernail will become the size of a mushroom, then a doorway, until finally, that fingernail-sized ornament will become a full-sized village, enclosed within itself.

As he walks through the village, Agapois continues to observe every member is grown from its immediate context. There is universal aesthetic that lacks any rules, yet there is a sense of emotional coherence. Apertures, arches, and towers mean nothing here. The representation of forms moves between different families of communication and fuses the language of architecture. The inhabitants of this colony appear to have some kind of value that bind them, although Agapios is not sure what they are.

Agapios finds a dweller painting the side of his home. “My name is Agapios. I have just met someone who told me that all structure must adapt to their situation in time. Is that true for this world?”

“Why, of course!,” said that painter. “Look at this image I’ve helped create! It is not my hand creating the figure, but the impulse of the environment flowing through me that directs my hand. My work and I are the product of this environment. It mutates and transforms me, as I shape it with my artistic hand.”

“But where does the material come from?,” Agapios asks.

“Anything that is real is a shadow of the singular divine. All things are generated, through generations! Design is not planned, design is unnatural!”

A craftsman approaches, “Stop with all your nonsense, you painter. Do not preach to our guest about religious values, revealing our secrets.” The craftsman turns to Agapios and introduces himself.

“My painterly friend can only explain so much. His picture is really worth a thousand words. This village was created organically, but it has nothing to do with its image. The real secret of the recipe of how this place was created is simple—it was all built one small step at a time. The secret ingredient, of course, is care.”

Agapios is intrigued by the builder but still questions the source of the matter. He spots a large monastery with a vaulted ceiling ahead. He enters to find a tiling system much more complex than the packed circles before, still without overlap, but now without gaps. All of the tiles are self-similar, meaning their same pattern occurs at smaller and larger scales. Agapios is alone in the monastery and studies the self-similar nature of the forms. In the middle of the courtyard is the form he notices on the tops of all of the buildings. Inhabitants were gathered around praying to it. The church officials told Agapios the forms’ purpose was to take their souls to a new dimension.

Agapios reconsiders what it means for something to be organic. Surely, words themselves cannot be organic because although their meanings change over time, their form does not. This is partly why Agapios finds such pleasure in numbers. Numbers exist in the realm of ideas, in which their meaning never changes; yet their physical form has the capacity to be represented in infinite ways. Would the same be true for ones’ soul?

4. Bulk

Agapios’ soul drifted out into endless dark space. In the distance, Agapios saw something coming toward him. He identifies yellow and blacks strips as a caution. As it got closer, the slower he could breathe. The wind was dying and the temperature was dropping. What appeared in the distance to be a tiny speckle was an entire universe. It consumed Agapios and he was now inside. After a brief moment of calmness, Agapios realized time was standing still.

Agapios does not know if inhabitants can live in this environment, yet through some dark energy, it feels alive and Agapios is bound to it. The forms interlock with one another, leaving no distinction of what is inside or out. Bulk exists in all directions.

There was no difference between the air and the frozen statues in front of him. Every time Agapios thinks he sees a moment of space, he realizes it is nothing but a black mass. Colored forms pack the entire area. Agapios always thought of space as something occupied with ideas and concepts anyway, so it wasn’t that strange.

“Hello, I am the architect. Do you like what I have created?” Agapios could hear a voice but did not know where it was coming from.

“Where are you? I would like to talk to you face to face,” responds Agapios.

“You cannot see me. I am in a higher dimension. You are on a brane with a single dimension and my bulk is warped into your space.”

“So architects do not design buildings where you are from?,” asks Agapios.

“No, we create models—models of space and time. Architecture is a symbolic discipline mediating what one can imagine, and what one can create in reality. People typically think of architects designing for a singular object. Instead, think of that object as the summit of a mountain. As model builders, we are less concerned with the final object. Instead, we are the trailblazers that find ways to connect to the ground below. We are not ones to give instructions, but create new recipes. Here is a model I created to experience a world without gravity. Press the red button on the gray surface and you will see.” At the moment, Agapios saw the red button right in front of him and forcefully pressed it.

The ground dropped from beneath him. Agapios was no longer stuck in the mass but falling in space indefinitely. After the bulk was out of sight, there were no reference points so he could not tell if he was moving fast, slow, up, or down. For all he knew he could be stationary. Eventually Agapios managed to see a small universe spinning in the distance.

5. Ecology

Finally! A clear radial plan—gyroscopic in dimension. As the world spins, Agapios enters a rotating realm. The orientation of forms always points towards a three dimensional center. It was as if the world he once saw was a flat plane, and a sphere had entered it. There was no sense of ground—more freedom for movement. Naturally, Agapios is used to experiencing the world from an upright position so it took some adjusting.

In this ecology, the buildings are moving characters that coexist and cooperate. They do not exist as entities separate from their environment, but coevolve with it. Connected to its infrastructure, the architecture revolves around a central axis, bending and conforming to its rotation. After Agapios’ initial observations, he comes to the conclusion that he and everything around him is freefalling while spinning! The question of time is less clear, but it sees as if it is looping back on itself.

Agapios feels as if he has been here before. Thinking back to his first transported environment... The tiny compactified, rolled-up dimension, on a mega scale! This is it!

Agapios is tempted to configure relationships between the geometries in front of him, but all of his calculations are astronomical! He continues to reflect to the first new realm he had entered and learned that physical laws are determined by their environment. His method could not rationalize the shapes in this realm.

Still, Agapios appreciated the strong sense of variety. Immediately he notices four unique species, working together to fulfill some sort of task, creating a single, open heterogeneous machine. There is no hierarchy, but a heterarchy amongst the individual components.

As a traveler, Agapios realizes he was not the center of his universe, but there are other centers, and those centers have centers, and so on. The true center is a void. With no center or edge, no being is more important than the other.

6. Debris

The gravity brane that Agapios was on began to warp—its three dimensional center was stretching into an ellipsoid. The strength of gravity seems dependent on location. Agapios realizes it would be even more impossible here to measure the geometry, because at different points, he would get different results!

The direction of objects allows Agapios to determine the flow of order. As the time passes, his sense of order increases. All of the small features help Agapios orient himself to his new environment. He first recognizes the red button he used to travel here. His existence is almost nothing in the vastness of this universe. Then, he sees environment’s first local inhabitant writing a poem*.

“We are free!”

“Free from gravity?” Agapios askes.

“No sir, gravity exists in all dimensions. What I am free of is my own thinking.”

“Doesn’t everybody have that freedom?”

“No. Freedom is not something inherited—it can only be discovered.”

“But there are so many ideas out in the world. How can we discover amongst all of the debris?”

“We take a handful of sand from the endless landscape of awareness around us and call that handful of sand the world. We must divide the world into parts and build our own structure of what the world is…that is freethinking.”

“But this landscape is so vast and complex, how one bring order out of this chaos?”

“This chaos is a part of all of us. You must not forget that and enjoy the moment. See the figure in the landscape that interests you. Not seeing any figure is not to see the landscape at all. It is especially important to beware the figures in the landscape because this multiverse is prone to invaders known as the black spirits. They are known to take energy and resources from this environment and bring it back to their world.”

Agapios looks up to the sky and sees the invaders. He becomes abducted…

Agapios had always believed himself to be destined for something greater than his time. Although he realizes the world is much larger than he imagined, his self-conviction grows like a tree upward while his roots grow down into the past. As a child, Agapios did not listen to stories because he wanted to learn, but to become a part of them. He did not think that they would actually become true…

7. A Musical City

The black spirits fly Agapios through the clear skies. The main tower opens before them as they enter the city. Agapios sees the same red button, which raises a gate.

The black spirits explain that in this dimension, everything must keep moving and nothing sits still. It is a musical and microscopic environment composed of vibrating strings. All forms retain rhythm to create expectation. Once that expectation is broken, music is created. Agapios is lost in the sound.

One of the musicians in the city stresses to Agapios the important of flow.

“Flow is when one gets lost in something—everything becomes automatic. In any activity, the process of getting to the final goal is always more important than the final goal itself. So you see, you must act in the moment!”

The black spirits return to show Agapios what life would be like without music or variation. The world becomes silent…

8. A Modern City

This is strangest place he has encountered thus far. Agapios arrives inside a blinding white box, devoid of any ornament. He has no idea the purpose of the space he is in. As a student, Agapios could not imagine a worse environment for learning; it lacks any visual information or cognitive nourishment. He looks outside and sees all the exact same rectangles. Three-dimensional grids perfectly and mechanically repeated. The entire world is a black and white grid; nothing but ones and zeros.

Agapios feels every person is trying to conform to be exactly the same one. Agapios stops someone in the street.

“Excuse me, sir, do you consider yourself an individual?” Agapios asks.

The man in a black suite smoking a cigar responds, “the individual is losing significance, his destiny is no longer what interests us.”

Agapios walks along the a new street where every building is exactly the same, except instead of a blank grid, the single repeating form is one of the most beautiful he had ever seen. Agapios contemplates its monotonous repetition and he finds less and less pleasure in it as he moves along, seeing the same thing, day after day…

He learned beautifulness and ugliness were not opposite value, but opposite stimulation. Being a part of a different reality, everything was stimulating, thus he believed everything to be beautiful.

9. An Imperfect city

The black spirits condemned Agapios to a two dimensional world, otherwise known as Flatland, or Two D Land.

Agapios drifted through the flat city and noticed all the lines were crooked and shapes were irregular. This is the most human condition he has experienced. An entire city built off of mistakes. Some forms were left unfinished. Agapios had never seen such perfection from something so incomplete.

Since the world was only along two axes, height could not be experienced, expect for one mountain. Agapios patiently climbed a steep hill to get there only to realize there was a much larger one ahead. The mountain grew. Agapios has never used his walking sticks more purposefully. He remembered his conversation with the architect. He does not expect to find any sense of fulfillment at the top of the mountain. As Agapios travels uphill, the crooked lines become straight. In reality, the lines remained crooked, but Agapios was surrendering. At every summit he reaches, there is a new summit to reach towards, but he is accepting and the effort is what he enjoys.

Drawing on Creativity

Today’s trend of reducing risk and increasing efficiency has resulted in the decline of imagination and intuition as a human condition. Historically, architects do not make buildings—they make drawings. Although BIM technologies challenge this notion, drawing is the most immediate and direct translation of an architect’s ideas. Architecture must find new ways to inject spontaneity and unpredictability into the world. Reexamination of the sublime reveals drawing and ornamentation as essential creative outlets for architects to promote a culture of stimulation and speculation.

Drawing is a primitive and humanist act that is not only about innovation, progress, representation, or instruction, but also rather novelty and introspection. There is value in drawing architecture that does not consider empirical restraints of site, budget, gravity, or program. When considering drawing as an experimental craft and unstructured activity, the language of lines and texture exist as realms of their own. In the tradition of ‘losing oneself’ in the creative act, drawing is not only about getting specific ideas on paper, but realizing form by withdrawing from being an ‘outside appearance maker’ and becoming one with the drawing—allowing the creation to design itself. In Authorship and Individual Talent, T.S. Elliot argues that acting out of instinct engages a process of depersonalization, which is a “continual surrender to the vast order of tradition.” Elliot continues to pose that tradition represents a ‘simultaneous order,’ in which “the existing order is complete before the new work arrives”(1). Such an inborn process calls to question the problem of control and to draw without constraints.

When creating architecture [as drawing or building], one can choose to work with or against material. If one chooses to work with the materials, ornament is simpler and reflects the natural beauty of the material. Adolf Loos, for example, describes ornament as emerging directly from natural forms and technical processes (2). On the other hand, working without regard for material expresses the will and imagination of the creator, which introduces the ‘art’ to the material. The degree to which it appears ‘artistic’ is not dependent on the material. Instead, the creative contribution is indeterminate, or boundless to the artist and material. Conversely, craft is something under the maker’s direct control. The problem with a purely craft-oriented approach to creating is that, as James Trilling describes, “virtuosity denies the power of materials, and thus reality because it represents control as an end in itself, the antithesis of inspiration”(3). Concerning T.S. Elliot’s essay, order is learned through inspired practice. Whether through hand drawing or digital modeling, creativity is not a gift. According to Malcolm Gladwell’s 10,000 Hour Rule, 3 hours a day for ten years of “deliberate practice” are needed to become world-class in any field4. Architecture has the potential to offer the public a practice of art and craft that embodies the effort to form new entries into reading the environment.

The term ‘order’ has always had particular importance for architects. For Louis Kahn, order is, “a creative level of consciousness forever becoming higher in level. The higher the order, the more diversity in design”5. Mies van der Rohe described architecture as a way to, “create order out of the desperate confusion of our time”6. For the purpose of this discourse, order is the perception of connectedness between objects and events. Consilience as a meme is trending in recent ecological theories, including Timothy Morton’s concept of ‘interconnectedness’ and totality. For Morton, totality is not a closed or complete system with a predetermined or fixed goal. Instead, interconnectedness involves facing meaninglessness and uncertainty. Order, in this sense, can build from contrasts between concert and discord, rational and irrational, known and unknown, seen and imagined. Ornamentation can be considered the embellishment of a personal order. Although ornament [drawn or built] may be beautiful, its purpose is not only to inspire aesthetically, but also to bring order out of ‘chaos’—or at least scale down its resistance.

Although philosophically humans are thought of as rational animals, humans have a limited capacity for comprehending the vastness of the physical universe. There is a lineage of this thought that traces to Edmund Burke’s and Immanuel Kant’s work on the sublime, yet that was before we could detect macro and microscopic universes (7,8). Art and the development of ornament are forays into an infinite, sublime universe. An artist can tries to escape this vastness through imagination the same way one attempts to escape morality through love. In both cases, for the lover and the artist, the way one responds consciously may not be the truest expression.

The tradition of ornament is an exemplary case study in the intention to unleash true expression by releasing constraints of tradition in thought, line, and form. Since the shift from the Greek to the Roman orders, this pedigree was reimaged several times in the course of history in decorative attempts to suggest lineage with the mythos of the past echoing in the present. Postmodernism was the weakest of all of these revivals in that its ornament was mostly concerned with the surface of things as opposed to their essence. Such a superficial approach is problematic because ornament was applied as decoration or an aesthetic addition. Another problematic form of post-modern ornament was that, though it flirted with public recognition, it was inevitably an elitist, and internally discussed, intellectual discipline, which was inaccessible to the public. The exclusive nature of post-modern ornament was a rupture from the origin of ornamentation as a communicative device. Originally, ornament was a coded narrative of the relation to space and the humans that made it. The sense of connectedness not only helps users orient themselves within their environment but also enriches them with poetic imagery and the creative impulse of the maker. In a society where information is readily accessible through smartphones and media, it is especially important to recognize and reveal what is genuine.